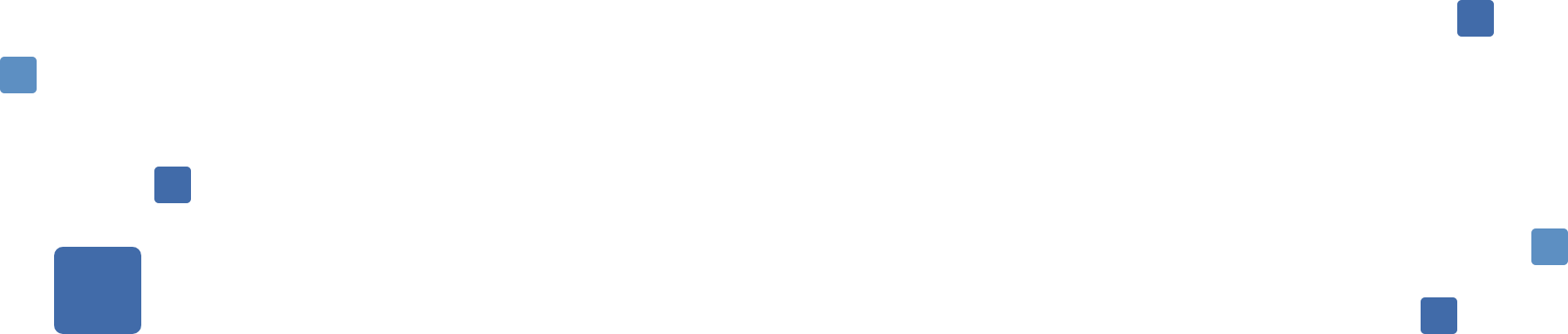

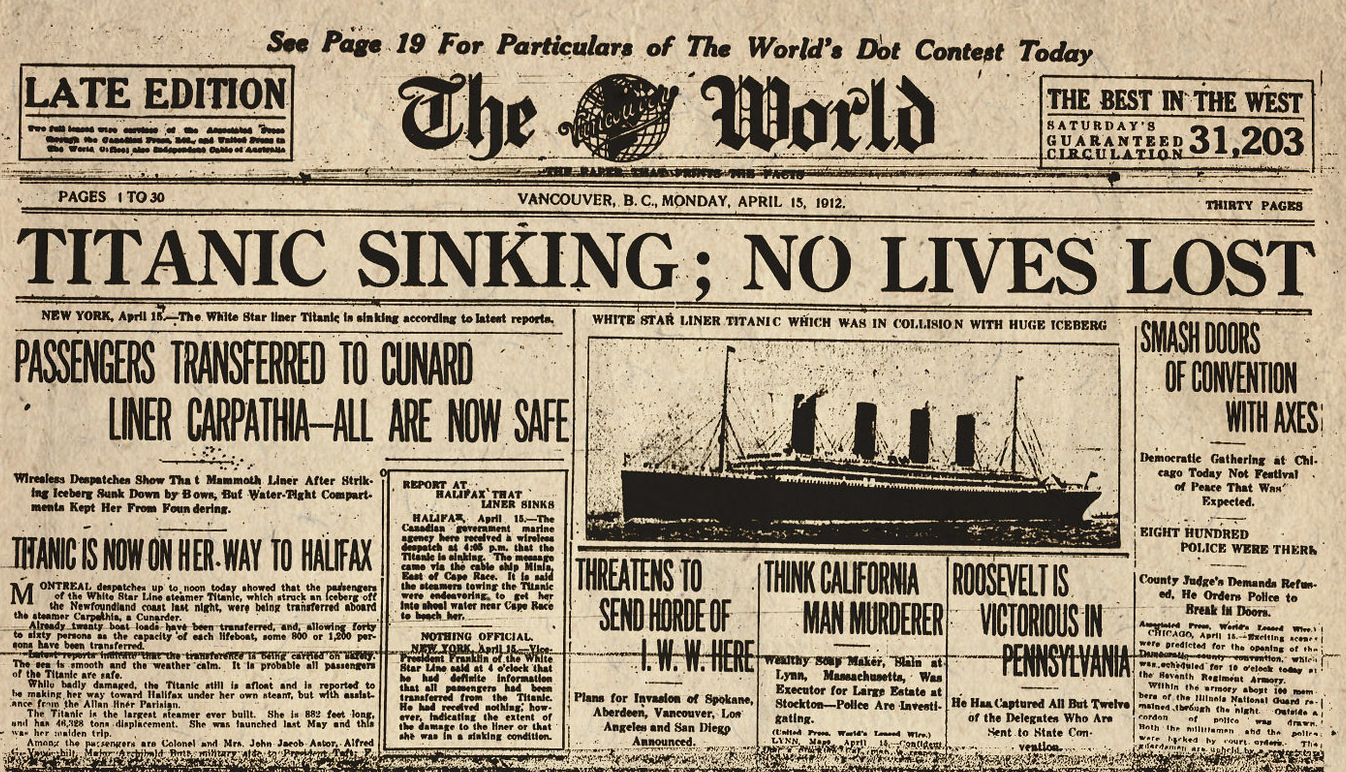

The sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912, is etched in history as one of the most devastating maritime disasters. The tragedy, which claimed over 1,500 lives, sent shockwaves across the globe, making headlines in every corner of the world, with newspapers of all sizes providing extensive coverage of the event. In the immediate aftermath of the Titanic disaster, the world’s newspapers were awash with headlines reflecting shock and disbelief, gripped by a wave of confusion and uncertainty. The early dispatches from news outlets around the globe were marked by a touching optimism, a hopeful belief that the “unsinkable” ship could somehow withstand the unthinkable. These early reports, published on April 15, 1912, the day the Titanic sank, were filled with conjecture and unconfirmed information. The lack of reliable communication technology and the sheer remoteness of the disaster site contributed to the spread of misinformation. Many reports suggested that the Titanic was being towed to Halifax, that the passengers were safe, and that the situation, while serious, was under control. “NO LIVES LOST,” a London headline reassured in the confusing early coverage.

This optimism was not entirely unfounded. After all, the Titanic was touted as the most advanced and safest ship of its time. Its state-of-the-art design and safety features, including watertight compartments and an advanced wireless communication system, led many to believe it could survive even a significant accident. However, as the hours ticked by, the grim reality of the situation began to emerge. The New York Times, one of the leading national papers, led the coverage with a somber and factual headline: “New Liner Titanic Hits an Iceberg; Sinking off Newfoundland with All on Board.” This straightforward approach was characteristic of larger, urban newspapers, which prioritized conveying the gravity of the tragedy to their readers.

By April 16, the optimism of the previous day had largely evaporated. The dispatches now reported the unthinkable: the Titanic had sunk, and the loss of life was catastrophic. The shift in tone between the reports of April 15 and those of April 16 is a stark reminder of the initial disbelief and subsequent horror that the disaster provoked. The early optimism was replaced by a grim acceptance of the scale of the tragedy. The Titanic, once a symbol of human achievement and progress, had become a stark reminder of human vulnerability and the unforgiving power of nature. A Kentucky newspaper headline solemnly summed up the human cost: “Millionaire and Peasant, Shoulder to Shoulder, Go to Their Death…”

Smaller, local newspapers provided a more varied perspective, reflecting their diverse readership. For instance, The Hartford Courant in Connecticut reported, “Titanic Sinks Four Hours After Hitting Iceberg,” choosing to emphasize the unexpected speed of the disaster. On the other hand, the Idaho Statesman opted for a more human-focused angle, with “1,500 Perish When Titanic Sinks; List of Survivors Includes Noted Men,” highlighting both the immense loss of life and the societal status of the survivors while combining factual reporting with elements of local interest to engage their readership. Community newspapers have always played a crucial role in shaping the narrative of local communities. They not only report on local events but also provide a localized interpretation of national and international happenings. The Titanic disaster was no exception. Community newspapers across the United States and the world reported on the tragedy, often highlighting local connections to the event. These local perspectives offer a unique lens through which to view the Titanic disaster. They reflect the concerns, interests, and values of their respective communities, providing a nuanced understanding of the event.

One local narrative that captured national attention was that of the Douglas family from my hometown of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

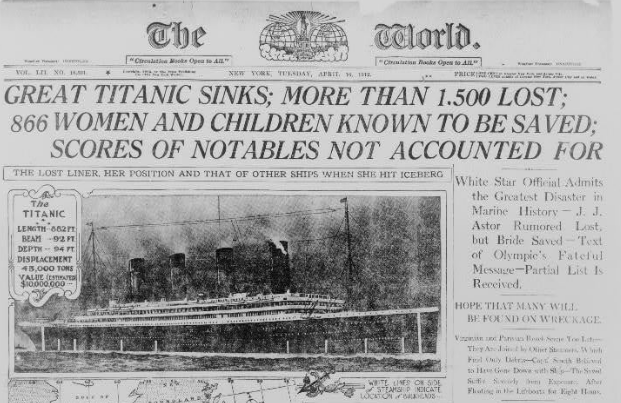

In the early 20th century, the United States was a hotbed of technological advancements, opening avenues for novel industries. Cedar Rapids, with its close proximity to agricultural resources, was no exception. The burgeoning railroad network facilitated easy procurement of supplies and efficient distribution of products. The Douglas family had relocated to Iowa to invest their substantial wealth in agriculture-dependent businesses and benefited from a highly educated workforce, primarily composed of German and Czech immigrants seeking opportunities in America. George Douglas Sr., an immigrant from Scotland, had initially worked for the railroad builders in Iowa. Leveraging the railroads he helped build, he co-founded a cereal company with Robert Stuart, manufacturing oatmeal and other cereals. This venture eventually merged to form The Quaker Oats Company in 1891.

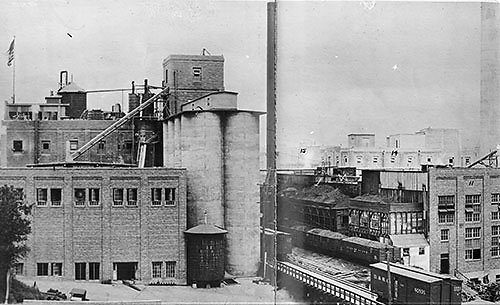

Initially working in their father’s cereal business, George Sr.’s two sons, George and Walter, would join their father at Quaker Oats, with Walter becoming an executive of the company and the younger George becoming a partner in The Quaker Oats Company. The Douglas brothers, George and Walter, had witnessed their father’s success in this evolving landscape. Inspired by their father’s entrepreneurial spirit, George and Walter Douglas embarked on their own business journey. In 1894, they established Douglas & Company, producing linseed oil. They managed the company until 1899 when they sold it to the American Linseed company. The entrepreneurial itch didn’t leave the brothers, and in 1903, they launched the Douglas Starch Works. The company produced various products, including cooking starch and oil, laundry starch, animal feed, soap stock, and industrial starches. By 1914, the Douglas Starch Works had grown to become the world’s largest starch company. By May 1919, the company boasted over 650 employees and processed 20,000 bushels of corn per day.

The Starch Works plant, located on the Cedar River banks, spanned ten acres and comprised 36 buildings. World War I brought about a surge in demand for corn products as substitutes for butter or lard due to rationing. The U.S. Food Administration promoted the use of corn over wheat products, significantly boosting the company’s revenue. Corn oil and cornstarch became indispensable cooking ingredients for homemakers, bakers, and cooks, used in making puddings, pie fillings, sauces, and baked goods. Douglas & Company products were widely advertised in popular publications like Good Housekeeping, The Ladies Home Journal, and The Saturday Evening Post, reaching millions of potential customers.

Walter Douglas had amassed a wealth of at least $4 million through his ventures in Cedar Rapids and his expansion into the linseed oil business in Minneapolis. His business affiliations were extensive, including the Saskatchewan Valley Land Company, Canadian Elevator Company, and the Monarch Lumber Company. Walter, his wife Mahala, and their French maid Berthe Leroy embarked on a three-month European journey. They secured first-class tickets for their return to the United States on the Titanic. The trio boarded the Titanic at Cherbourg, with Mahala and Walter residing in cabin C86. On the fateful night of the sinking, Mr. and Mrs. Douglas were in their cabin. The impact of the collision was said to be so subtle that most first-class passengers barely noticed, and Walter and his wife paid very little attention to it. Mahala would later testify in front of Congress on May 2nd, 1912:

“The shock of the collision was not great to us; the engines stopped, then went on for a few moments, then stopped again. We waited some little time, Mr. Douglas reassuring me that there was no danger before going out of the cabin. But later, Mr. Douglas went out to see what had happened, and I put on my heavy boots and fur coat to go up on deck later. I waited in the corridor to see or hear what I could. We received no orders; no one knocked at our door; we saw no officers nor stewards – no one to give an order or answer our questions. As I waited for Mr. Douglas to return, I went back to speak to my maid, who was in the same cabin as Mrs. Carter’s maid. Now people commenced to appear with life preservers, and I heard from someone that the order had been given to put them on. I took three from our cabin and gave one to the maid, telling her to get off in the small boat when her turn came. Mr. Douglas met me as I was going up to find him and asked, jestingly, what I was doing with those life preservers. He did not think even then that the accident was serious. We both put them on, however, and went up on the boat deck.”

At approximately 11:35 PM, lookout Frederick Fleet spotted an iceberg. Despite Chief Officer Murdoch’s immediate orders to reverse the engines and execute a hard turn to port, there was no hope of avoiding the massive iceberg that extended above the water between 50 to 100 feet high with a length of anywhere between 200 to 400 feet. It is estimated that there was only about 60 seconds from sighting to hitting the iceberg. Given that it would take between two and two and a half minutes for the Titanic to stop, covering a distance of up to 1 mile to do so, the collision became unavoidable. The crew of the Titanic prematurely celebrated as they felt that they had averted disaster as the ship scraped the iceberg slowly along its starboard side. They reasoned that even if there was some hull damage from the seemingly minor brush against the ice, the Titanic was engineered to stay afloat even if five of its watertight compartments were filled with water. However, the unfortunate reality was that rivets had burst in six compartments, allowing tons of water to flood into the Titanic’s depths. The ship, along with 1,503 souls on board, had a mere three hours left before succumbing to the icy depths of the Atlantic.

Nearby, the RMS Carpathia’s wireless operators received a distress call from the sinking Titanic. Captain Arthur Rostron immediately ordered the ship to change course and steam full speed ahead through the perilous ice field to the Titanic’s last known position. After navigating through treacherous ice floes and racing against time, the Carpathia arrived at the scene around 4:00 a.m. on April 15th, approximately two hours after the Titanic had sunk. The crew of the Carpathia managed to rescue 705 survivors from the lifeboats scattered across the freezing Atlantic waters.

As the news of the disaster began to unfold in the subsequent hours and days, the details and facts were slow to emerge. The tragedy was closely monitored by local and national press, with publishers releasing headlines and articles that often reflected speculation rather than concrete facts. Initial reports were filled with confusion and misinformation, a common occurrence in the early stages of a disaster. The Des Moines Register, one of Iowa’s most prominent newspapers, initially reported that the Titanic was being towed to Halifax and that all passengers were safe. This was based on erroneous wireless reports that were widely circulated in the immediate aftermath of the disaster. The Titanic disaster occurred at a time when wireless technology, which would become ubiquitous, was just taking hold. As the stricken ship’s messages were picked up, sometimes by amateurs with Marconi receivers, news traveled lightning fast, though sometimes it got garbled. This led to some initial reports of the ship being towed to Halifax with everyone safe, the result of two unrelated fragments of information being picked up by a wireless station in Massachusetts and misinterpreted.

When the devastating news of the Titanic’s sinking reached Cedar Rapids, a glimmer of hope still lingered for the survival of Walter and Mahala. The Cedar Rapids Gazette regularly updated its readers on the Douglas family’s fate, reflecting the local community’s interest in their story. On April 17, The Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette reported:

“Up to 1 o’clock today, no definite news had been received in Cedar Rapids concerning the fate of Mr. Walter D. Douglas…. The wireless telegraph companies had great trouble in effecting communication with the Carpathia…. It appears that a considerable number of the first and second cabin passengers, especially the men, must have perished, but it is still hoped that Mr. Douglas was among the ones rescued. Mrs. Douglas is on the Carpathia, but whether Mr. Douglas went down with the boat, as did many others of the male passengers, remains to be determined.”

As the days passed, however, optimism for Walter’s survival began to wane, replaced by a growing sense of dread. Later accounts would paint a more detailed picture. Receiving no instructions to go topside, the couple returned to their cabin, the crew assuring them that there was no danger. As their predicament become more apparent, they decided to make their way to the deck of the ship, where Mr. Douglas saw his wife and maid off in a lifeboat but refused to go himself until all women and children were accounted for, saying it would make him ‘less than a man’ or ‘No, I must be a gentleman.’ According to subsequent reports, Walter Douglas, dressed in his best attire, assisted in lowering the last lifeboat of survivors. His body was recovered in the days following the disaster. As a first-class passenger, he was easily identifiable, which saved his body from a sea burial. Instead, his body was embalmed and transported to Canada aboard the Mackey-Bennett. It was later brought to Cedar Rapids for interment in the Douglas family mausoleum at Oak Hill Cemetery. His wife, Mahala Douglas, and their maid survived the sinking. Mahala was the first survivor to board the RMS Carpathia in the early hours of April 15.

On April 16th, in a desperate bid for information, Walter’s brother George and his wife Irene embarked on a journey to New York. Their destination was the dock where the Carpathia, the ship that had picked up the Titanic’s survivors, was due to arrive. The couple held onto the hope that they would find Walter and Mahala among the survivors. The night of April 18th was fraught with tension as the Carpathia finally docked at Pier 54, the very berth that had been intended for the Titanic. Among the weary survivors disembarking from the ship was Mahala, but there was no sign of Walter. The sight of Mahala walking down the ramp by herself confirmed George’s worst fears – Walter had not survived the disaster. George mourned the loss of his brother, but his grief could have been made so much worse if he were to have lost a child as well. Howard Bruce Douglas, the son of George and Irene and nephew to Walter, was spared from the Titanic disaster by sheer luck. Having completed a tour of Europe, Howard was ready to return home. He had told his parents that the ticket for the Titanic was not just a passage back to the United States but a ticket to be part of a historical event – the maiden voyage of what was then the world’s largest and most luxurious ship. However, as fate would have it, an unexpected twist occurred. A business engagement, unforeseen and urgent, demanded Howard’s attention. This professional obligation forced him to alter his plans, requiring him to delay his journey back to the United States. At the time, this change of plans seemed like a mere inconvenience, disrupting his schedule. Little did Howard know that this seemingly minor alteration in his itinerary was a twist of fate that would spare his life.

In the days to follow, Mahala shared her perspective on the events of that fateful night and brought new details to light, many of which garnered national attention. In a poignant account published by the New Jersey newspaper, the Rahway Daily Record, William H. Randolph, a resident of the city and an employee of Walter Douglas, shared a distressing narrative of the shipwreck he heard from Mrs. Douglas. In her interview, which was published in the paper on Friday, April 19th, 1912, she made a startling revelation about Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, encouraging Captain Edward Smith to sail at top speed despite warnings of ice.

“Mrs. Douglas corroborates statements which have already been sent out as to the warnings which were sent to the Titanic of the presence of icefields in the vicinity of the vessel. She told Mr. Randolph that a marconigram was received by Bruce Ismay at least an hour before the vessel struck the iceberg telling him of the presence of large quantities of ice. In company with Mrs. Ryerson, one of the first cabin passengers, she saw Mr. Ismay read the dispatch, and Mrs. Ryerson then asked him what he intended to do. “Do you intend to slow the boat down?” asked Mrs. Ryerson of Mr. Ismay. “No, we’re going ahead at full speed,” was the reply Mr. Ismay made to her.”

Despite an order that only women and children were allowed in the lifeboats—of which there were only enough for about half of those on the ship, Ismay boarded the collapsible lifeboat C. He later claimed that no women and children were in the area, but eyewitnesses subsequently challenged that assertion. Ismay was publicly branded a coward and was largely shunned. In 1913 he retired from the White Star Line.

On my daily commute, I drive by the Quaker Oats plant, one of the cornerstones of our community, founded by the Douglas family. I attend events on the Brucemore Mansion’s lawn, the home where George and Irene live. To get to our local library, I drive by the Ingredion plant, the site George Douglas Jr. and his brother Walter originally established Douglas Starch Works in 1903, approximately where Ingredion sits today, after founding what became Douglas and Co. in 1894. There are countless more locations around the city with direct ties to the Douglas family, and my mind instantly travels back to the events of April 15, 1912, at the sight or mention of any of them. The story of the Titanic is no longer “something that happened to someone, somewhere far away”, it is part of my community’s history.

Cedar Rapids is far from unique regarding local connections to history. Connections to major events that impacted the nation or the world, like the Titanic disaster, are everywhere. In Iowa alone, more than 20 men, women, and children, hailing from diverse backgrounds and walks of life, shared ties with Iowa and the Titanic, although not many of them garnered the coverage or attention of The Douglas family. In stark contrast to the Douglases were the second-class passengers, including the Caldwell family. Albert and Sylvia Caldwell, along with their 10-month-old son Alden, were church missionaries who were returning to the Midwest from Siam, now known as Thailand. The Caldwells had decided to return to the United States after Albert fell ill, choosing the Titanic for their journey home. Their survival story is one of courage and determination, a testament to their unwavering faith. The third-class compartment of the Titanic was filled with immigrants seeking a new start in America. Many were drawn to Iowa by the promise of jobs in the state’s flourishing farms and coal mines. Among them was Jelka Dyker, a young Serbian woman traveling to join her husband in Hiteman, Iowa. Jelka, along with many other third-class passengers, perished in the disaster, her dreams of a new life in America tragically unfulfilled.

Less than 2 hours away from Cedar Rapids is Burlington, Iowa. Gunnar Tenglin, a Swedish national, was among the passengers on the ill-fated Titanic, making his way back to his adopted home in Iowa. Tenglin, who was 25 at the time of the disaster, had migrated to America when he was 16. He found a home in Burlington, where he initially worked with ice-cutting crews on the Mississippi River, unable to speak English. His language skills improved while he was employed at the Horace Patterson farm. In 1908, Tenglin went back to Sweden, where he married Anna. The couple had a son, Gunnar, in Stockholm in 1911. The following year, Tenglin decided to return to Burlington and booked a third-class ticket on the Titanic.

Tenglin believed the third class on Titanic was equivalent to first class on most other ships. On the night of April 14, 1912, after returning from a party onboard the Titanic, Tenglin was getting ready for bed when he felt a jolt. He left his shoes and lifejacket behind when he went up to the deck. By the time he got there, all the lifeboats had been launched. Tenglin’s knowledge of English came in handy as he was asked to translate the officer’s instructions to other Swedish passengers. This, as reported in a 2012 Burlington Hawk Eye article, possibly saved his life as he was still on deck when the ship went down. The Burlington Daily Gazette interviewed Tenglin in 1912, who was described as a tall man with light blue eyes and brown hair, and he recounted the harrowing experience. He described how they found a collapsible lifeboat that could hold about 50 people. As they struggled to free it, the rising water launched the boat. The ordeal was far from over. Tenglin recalled how about 150 people were either swimming around the boat or clinging to it, causing fear that the boat would sink or collapse. They had no oars and were at the mercy of the calm sea. The passengers, standing in knee-deep freezing water, had to push away desperate people in the water to prevent the boat from capsizing. Tenglin also mentioned a large Swedish man named Johnson who was tasked with throwing bodies overboard to lighten the boat and increase its buoyancy.

On the other side of the state, one of the last survivors of the Titanic disaster, Helen Delaney, spent a significant part of her life in Council Bluffs, Iowa. However, she seldom discussed her harrowing experience on that ill-fated ship. Delaney’s extraordinary tale began when she was just four years old. As the Titanic was sinking, she was thrown overboard. Fortunately, someone managed to catch her, and she survived the night. Tragically, her parents did not share the same fate. While the family had embarked on the ship in England, the identities of Delaney’s birth parents remain a mystery. Delaney was unaware of her exact birth date, as reported by the Council Bluffs Daily Nonpareil in 2012.

Along with the other survivors of the Titanic, Delaney made it to New York on April 18, 1912. She was subsequently placed in an orphanage. James P. Delaney, a locomotive engineer for the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Rail Company (now known as BNSF) who resided in Council Bluffs, and his wife decided to adopt the young girl. She was brought to Council Bluffs via an orphan train sometime in the mid to late 1910s.

Exploring historical newspapers in your library’s Community History Archives allows you to delve into these local perspectives. These archives preserve the community newspapers of the past, making them accessible to researchers, historians, and the general public. By studying these resources, we can gain a deeper understanding of historical events like the Titanic disaster, viewed through the unique lens of local communities. These historical community newspapers offer invaluable insights into historical events like the Titanic disaster. They provide a local perspective on global events, reflecting the concerns and values of their communities. By exploring digital archives of historical newspapers, we can learn more about the era, the reactions, and the events from a local standpoint, enriching our understanding of history. In the face of national tragedy, smaller, local newspapers served closely-knit communities, adopting their tone and perspective accordingly. As these publications catered to specific communities, their coverage often mirrored local sentiment and interests. This strategy made them a vital conduit of information, fostering a sense of shared experience in the face of national tragedy. The coverage of the Titanic disaster in American newspapers, therefore, not only informed the public about the event but also served as a unifying factor during a time of national grief. The Iowa-Titanic connection serves as a reminder that the Titanic disaster was not just a tragic event in maritime history but a human tragedy that touched lives across the world, reaching even the heartland of America.

The story of Walter and Mahala Douglas and their fateful voyage illustrates how the Titanic disaster not only touched not only those aboard the ship but also the communities they left behind. The Douglas family’s legacy continues to be a significant part of Cedar Rapids’ history, their story forever intertwined with the tragic tale of the Titanic. The Douglas family’s story, and stories like theirs, live on in countless writings, documents, photos, and records in archives, shelves, and in storage that may not yet be in a searchable digital format. As more and more of these stories are digitized, more connections and discoveries will be made, creating new connections and painting more vivid pictures of events like the Titanic tragedy and the people involved. People who may be from your town, region, or state. People whose stories you can connect to. Stories that can make the events more “real” or tangible.

Mahala Douglas, the resilient survivor of the Titanic disaster, was not only a philanthropist and patron of the arts but also a talented writer. In 1932, she published a collection of stories and poems, a testament to her literary prowess and ability to channel her experiences into poignant written expressions. A copy of this collection, personally inscribed to George and Irene, is preserved in the archives of the Brucemore Mansion, serving as a tangible link to the past. The collection concludes with a haunting poem titled “Titanic,” which offers a chilling account of the disaster. Through her evocative words, Mahala transports the reader to the fateful night, painting a vivid picture of the serene yet foreboding sea, the star-studded sky, and the majestic Titanic, its lights shimmering in the darkness.

The poem describes the quiet before the Titanic disaster as a slow, unavoidable event, using strong imagery to show the scale of the disaster and the hopelessness of those on the sinking ship. The poem ends with silence, reflecting the tragic end of the Titanic and its passengers. Mahala’s poem is a touching tribute to the Titanic disaster, capturing its size and the deep sense of loss it caused. It serves as a strong reminder of the personal stories behind historical events, keeping the memory of the Titanic and its victims alive in literature. Through her poem, Mahala Douglas ensures that the story of the Titanic, and her personal link to it, continues to touch future generations.

Titanic

The sea velvet smooth, blue-black,

The sky set thick with stars unbelievably brilliant.

The horizon a clean-cut circle.

The air motionless, cold – cold as death.

Boundless space.

A small boat waiting, waiting in this vast stillness,

Waiting heart-breakingly.

In the offing a vast ship, light streaming from her portholes.

Her prow on an incline.

Darkness comes to her suddenly.

The huge black hulk stands out in silhouette against the star-lit sky.

Silently the prow sinks deeper,

As if some Titan’s hand,

Inexorable as Fate,

Were drawing the great ship down to her death.

Slowly, slowly, with hardly a ripple

Of that velvet sea,

She sinks out of sight.

Then that vast emptiness

Was suddenly rent

With a terrifying sound.

It rose like a column of heavy smoke.

It was so strong, so imploring, so insistent

One thought it would even reach

The throne of grace on high.

Slowly it lost its force,

Thinned to a tiny wisp of sound,

Then to a pitiful whisper….

Silence.