Preservation Is Every Bit As Important As Access

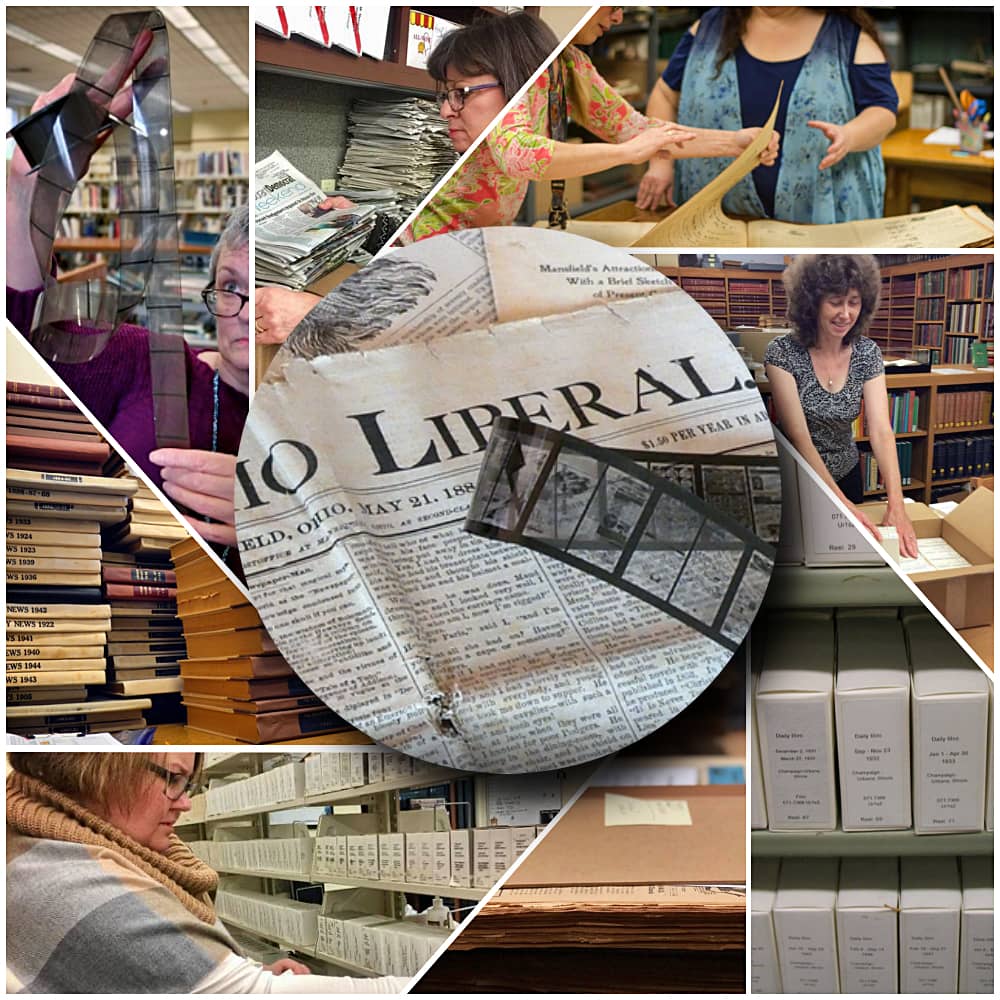

Digitizing your microfilm holdings and other documents of historical interest will unlock history by bringing it out of the drawer and putting it at your fingertips. However, access is only ½ the equation. Before you embark on a digitization project, you need to evaluate the risk to any original source materials in your collections.

Historical newspapers and documents provide the first draft of a community’s history. It is not history remembered or retold years later. It is not an oral account handed down. It is not an interpretation of a historian. It is the history recorded on the day of or in the days following. That allows us to watch “history as it happened” through the lens of the individuals who witnessed it firsthand and recorded it in their words.

It allows us to see how our community reacted to local and national events and how those events shaped not only our community but the nation and the world as a whole.

They also help us put people, places, and historical events in perspective. I often use the phrase “to understand the present; we need to take a look at the past.” This was and is especially true at times like these. Between the pandemic or civil and political unrest, it is eye-opening to compare them to events in American history that mirror them. The Spanish flu pandemic. The Civil Rights Movement. Polarizing political figures like Joesph McCarthy, Andrew Johnson, or James Buchanan. There are parallels everywhere, and because of those parallels, they give us a chance to see how far we have come and how far we have yet to go.

Genealogists have been pouring through newspapers for decades while doing their family history research. Scouring each page for birth and marriage announcements, death notices and obituaries, community events, and scholastic and athletic achievements.

And don’t forget my favorite: the “around town” blurbs. You know the ones: “Sally May was seen having a picnic under the old oak tree at Miller park with Johnny Jones, who is back in town for the weekend and staying at the home of Jhonny’s maternal aunt and her husband, Mr. Arnold Roberson. They had fried chicken and homemade potato salad, and both looked happy and satisfied when the meal was finished.” These sections of the newspaper were the “Facebook” updates of the era!

I have been in this business for a long time, and through the years, technology, methodology, and presentation have changed quite a bit. What has never changed is the importance of the content. The words printed in a community’s newspaper are so incredibly important. They allow us to connect with the past in a very tangible way. These words not only need to be made easily available through digital transformation and creating a searchable database, so it is available to anyone from anywhere…but they must also be preserved!

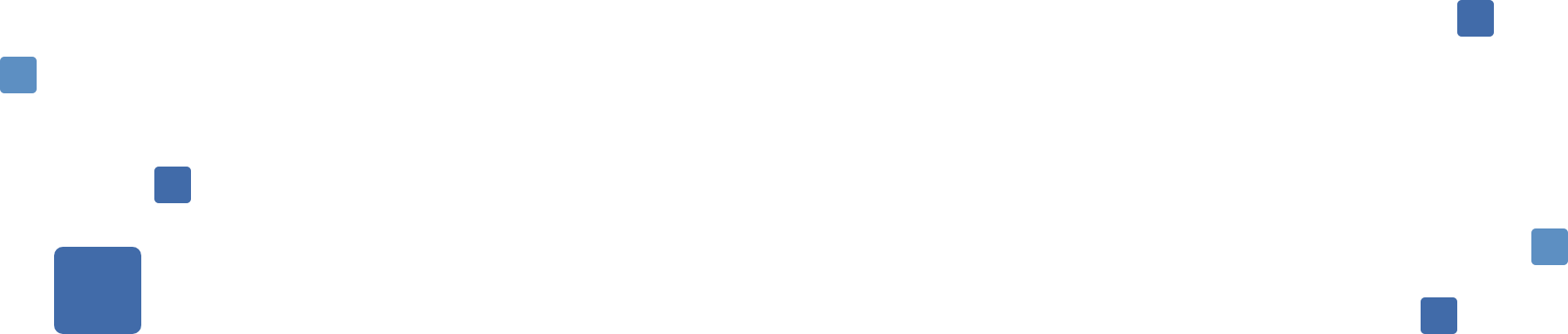

It goes without saying, but physical newspapers, either loose or in bound volumes, are at risk. Paper is fragile and not stable. Humidity, temperature variations, and other environmental factors accelerate the degradation of the paper, and the history recorded on it will eventually be lost unless steps are taken to ensure those words will be available to read for the generations to come.

Sometimes the older the newspaper, the better the condition you will find it. Most of the newspapers prior to the Great War were published on paper stock with a large percentage of cotton fabric. While these “rag” papers are more resistant to damage with the passage of time, they are also more susceptible to contamination from oils on the skin, leading to discoloration and fading of the print,

Newspapers printed in the early 1900s are brittle and fragile. Depending on the condition, even turning a page can sometimes “snap” a page in half or leave part of the page in your hand.

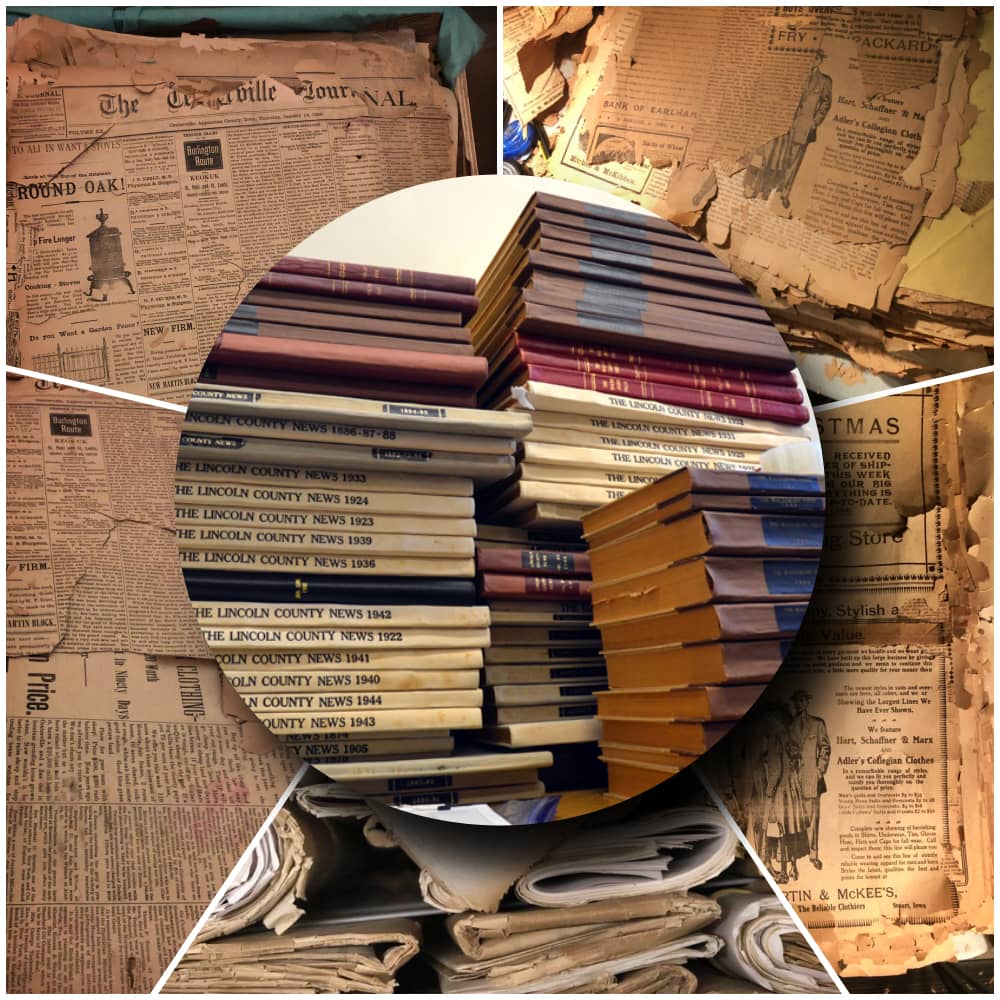

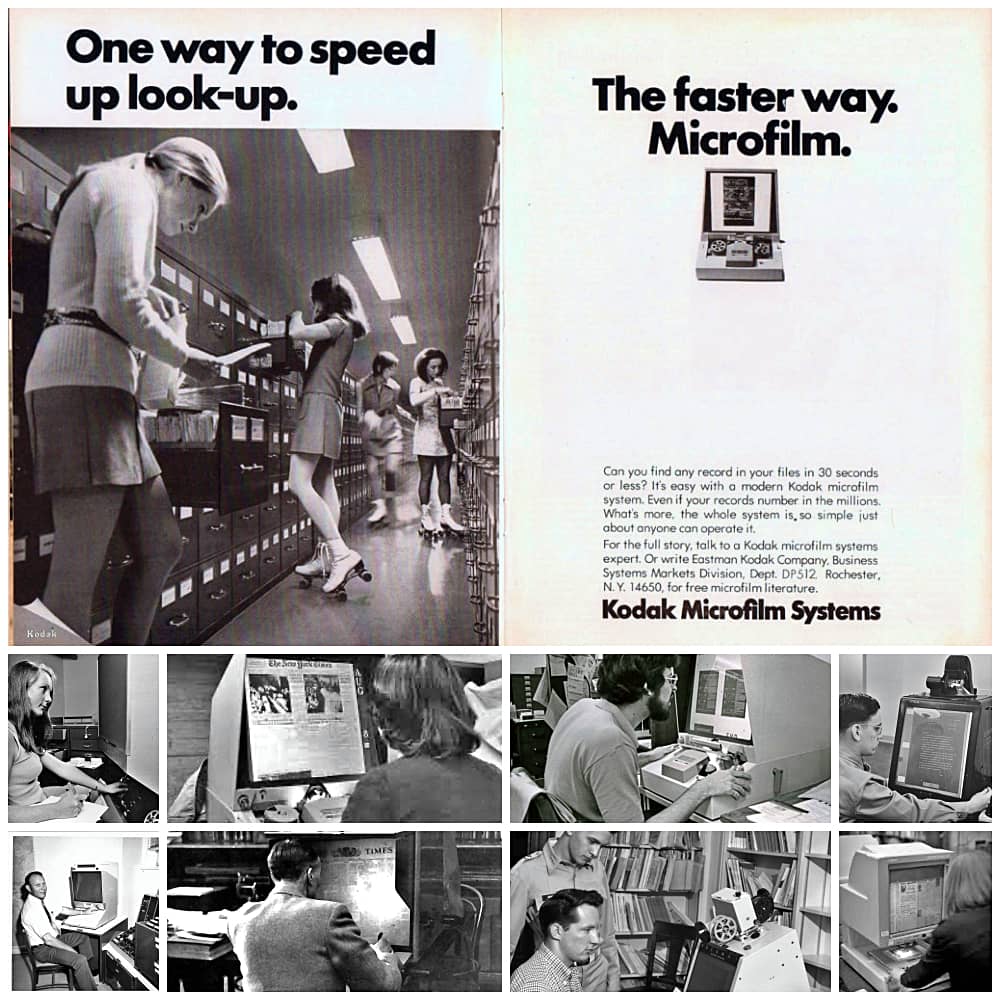

The only true way to ensure the survival of that printed history is through the preservation of microfilming. 35mm Silver Halide microfilm is considered the archival standard and offers a 500+ year life expectancy when captured and stored to standards. Archived content will be available for future generations and can be accessed by anyone with a magnifying glass and some light.

If digitization is a higher priority than preservation, I urge you to look at microfilm as your “analog backup” for your digital images. New digital images can be created from quality microfilm at any time, now or in the future. If a digital file is lost due to hardware failures, lack of redundancy, or absolution of technology, you can “restore” your digital image from your “analog backup” by rescanning the microfilm.

Properly preserved content on microfilm also will allow you to “upgrade” your archive as technology advances, processes become more efficient, and things like hardware, software development, infrastructure, and bandwidth become increasingly affordable.

If you have paper in your collection, microfilm is the “gold standard” for long-term archival preservation. But what if you already have your content preserved to microfilm? Did you know that your microfilm might also be at risk?

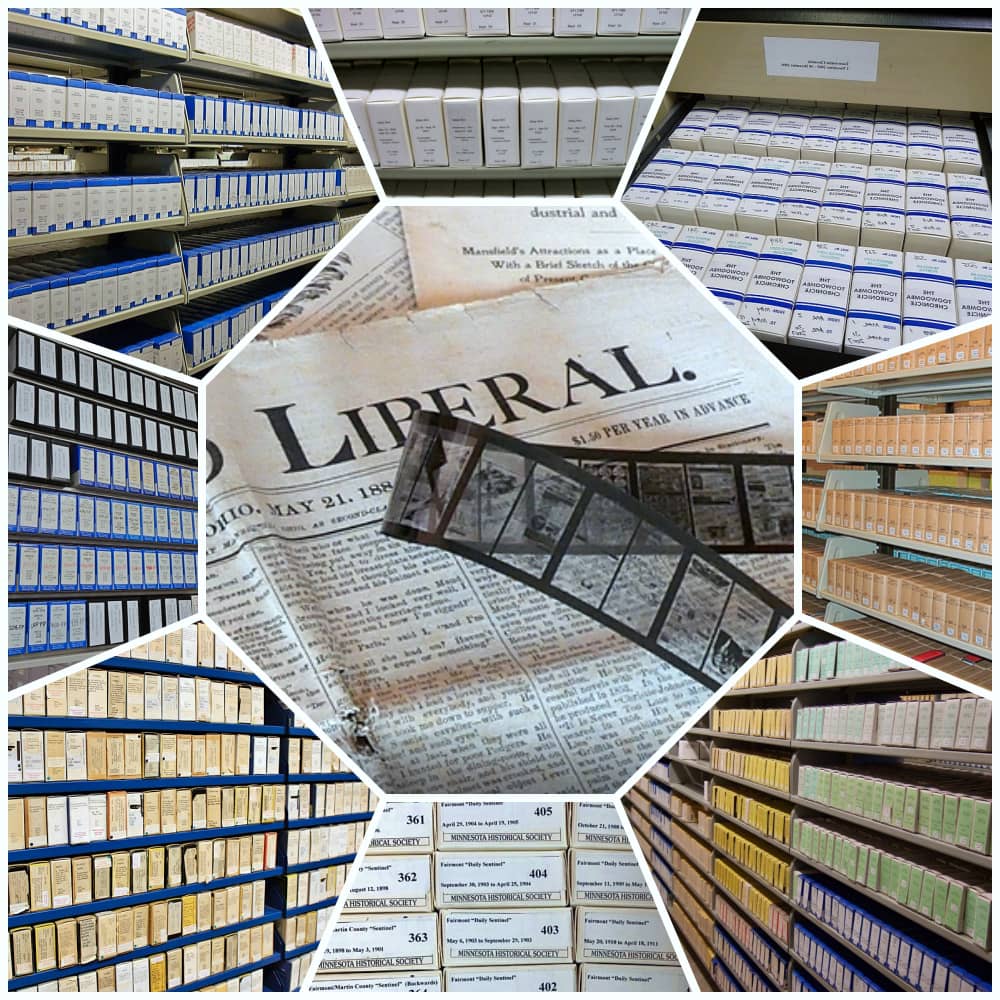

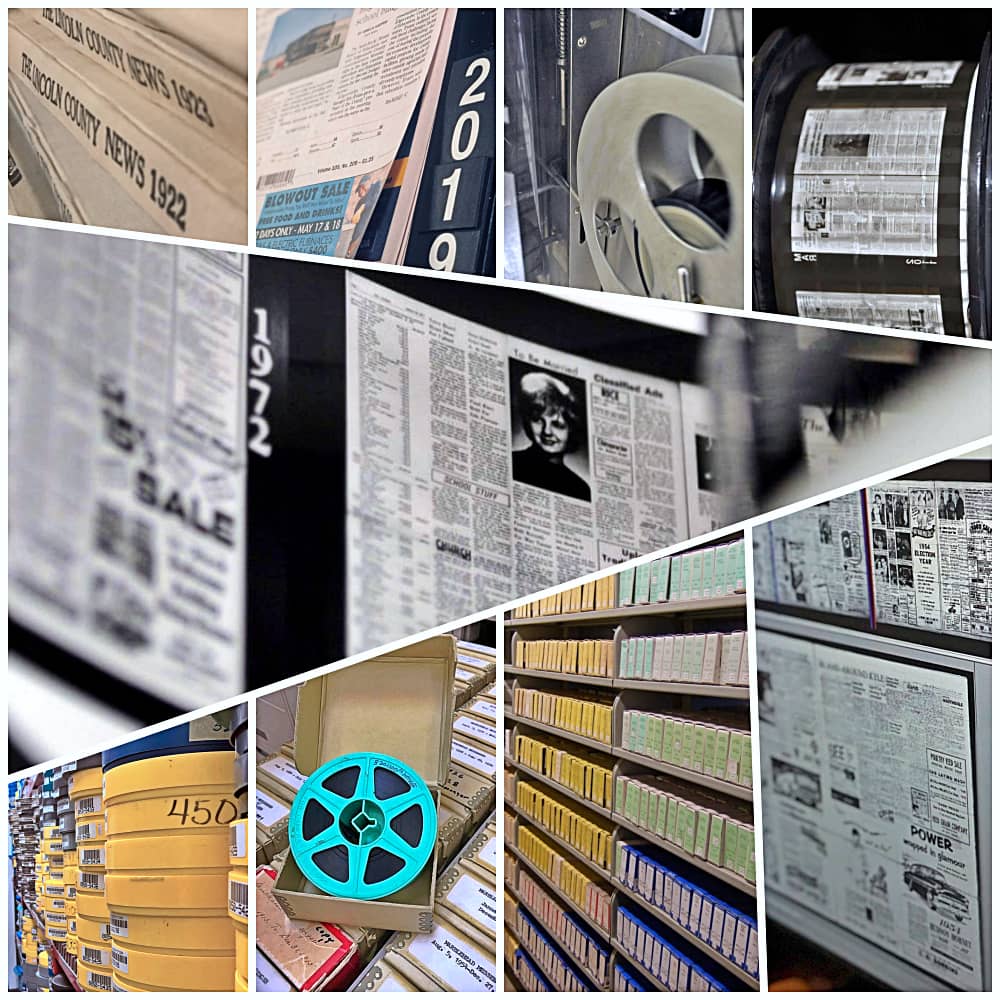

Microfilm is vulnerable to a “disease” known as “Vinegar Syndrome”, which is a chemical of degradation that occurs with cellulose acetate film. It takes its name from the obvious vinegar smell, which is the identifying characteristic of the degradation process. It smells like vinegar because infected film releases acetic acid, the same substance in common vinegar. Microfilm made with acetate backing is susceptible to vinegar syndrome. Most films of this type were made prior to 1980.

Vinegar syndrome is also “contagious.” If a reel in your collection is infected, the other reels it is stored with could “catch it” too. The autocatalytic nature of vinegar syndrome triggers the breakdown of any cellulose acetate film reels stored in proximity to each other.

Microfilm can also suffer from another condition known as “redox.” Redox describes the process that forms the blemishes caused by a localized, cyclic reduction and oxidation of the silver in the image area. Redox appears most commonly on microfilm but may also appear on prints made that used silver in the development process. Many kinds of defects and blemishes that occasionally appear on processed microfilm can be attributed to redox. Most commonly, redox blemishes are small circles outlined with concentric rings that alternate between dark and light. They are frequently in shades of brown or yellow and often seen centered on scratches in your film, sometimes closely packed, like water droplets on a spiderweb.

Proper storage can help mitigate the risk. To ensure your collection meets the 500-year life expectancy target, your microfilm should be stored in a temperature and humidity-controlled environment. This is difficult to do with your institution’s service copies, but steps should be taken to ensure there is a well-maintained microfilm master in addition to the service copy in your collection. You would be surprised how many clients embark on a digitization project, only to discover that the only available source material to scan is a scratched service copy because the master was either missing or damaged.

Ideal storage conditions for microfilm masters consist of a 67-degree base temperature that does not exceed 70 degrees with a constant relative humidity of 35%. These conditions should not vary more than 5% in a 24-hour period. The master film should be stored on 1,000-foot reels (as opposed to the 100′ reels used for your service copies) in a non-reactive container.

Only chemically stable materials such as non-corrosive metals (anodized aluminum or stainless steel), peroxide-free plastics, and acid-free paper should be used for containers to ensure no degradation is caused to the image. Container label information should include an identification number or barcode to allow for cataloging the location and contents.

I know resources and time are limited commodities in most organizations, and I certainly understand it is difficult to perform a full audit of the integrity of your film archive or evaluate existing acetate-based microfilm collections on an annual basis. I would, however, recommend that each year you randomly select a sample of not less than 2% of the total number of reels in your collection and do a quick “health check” on the film. Document any brittle film, microfilm with redox or other blemishes, the presence of vinegar syndrome, any discoloration, or any other condition that may jeopardize the life and longevity of your valuable archive.

If you know for a fact that your collection contains older films, I recommend you consider doing a larger annual sample. If you identify a suspect reel, immediately “quarantine” it away from your collection and test the reels stored in close proximity to the infected reel. A-D Strips are available to purchase from the Image Permanence Institute. These are dye-coated paper strips that provide a simple and safe method for detecting, measuring, and recording the severity of vinegar syndrome.

If you want to perform a more in-depth and thorough inspection, Guidelines for inspection are available and can be found in the ANSI/AIIM standards (section MS45-1990 can be purchased at the ANSI Webstore). In addition to common microfilm maladies, you may want to take the opportunity to check the reels for quality and adherence to standards. This includes counting the number of physical splices (and butt splices as opposed to overlap splices) and that there are no rubber-based adhesives contained in any tape material used. A content inventory can also be helpful to determine gaps in coverage, missing dates, and/or incorrect labeling.

I am of the opinion that microfilm should be used as a preservation tool and should be touched as little as possible. Obviously, the microfilm master should not be handled at all, as it is the archival copy, and should be tucked away in a climate-controlled environment, but I also encourage our partners to limit the use (if possible) of the service copies in their collection. This is where digitization comes into play. Digitization offers practical access to the content in your microfilm collection, making it widely available and limiting the wear and tear on your film.

When preparing original source materials for digitization, if you discover the available microfilm of the newspaper to be digitized is poor, or the edition has not yet been preserved on microfilm, then consider making filming your first priority. Newspaper digitization is most commonly done from microfilm as scanning from microfilm is generally faster and less expensive. I generally advise against using an institution’s service copies as a source material to scan from (if at all possible). These duplications are likely scratched or have surface damage from handling, and that will impact the image quality. Unfortunately, if the microfilm master is unable to be located or is damaged, sometimes the reel in your collection may be the only available copy. It happens more than you might think.

You can look at your service copy as a “second archival copy,” one that preserves the printed word in the unlikely the master microfilm, or other service copies in the wild, are lost, destroyed, or otherwise unavailable. They should be handled and used with care. Care patrons do not always exercise.

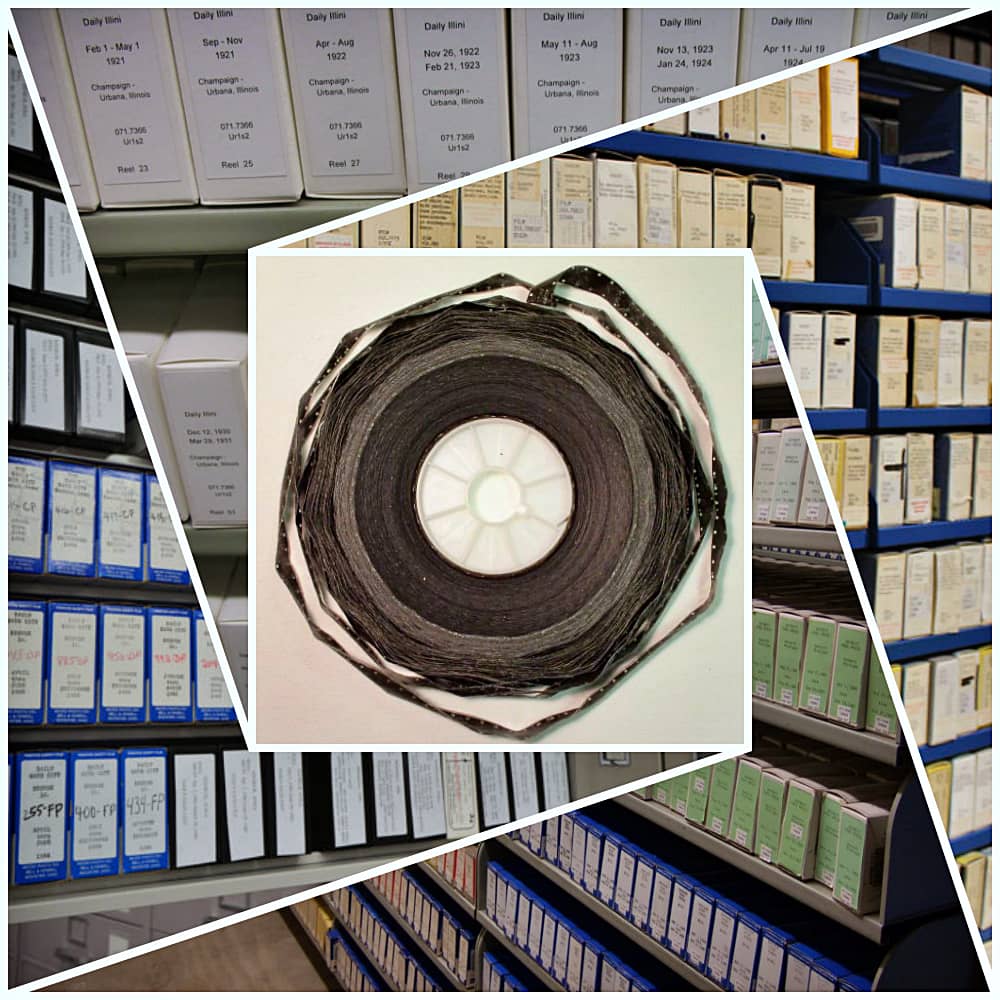

Rough handling leads to tears, creases, scratches, and breaks. Occasionally the reel will need to be replaced due to “wear and tear,” and purchasing a duplication made from the microfilm becomes necessary. Replacing one reel is relatively inexpensive; however, over time, replacement costs can add up. Damage can be caused by patrons abusing the high-speed motors and letting the film “flap” at the beginning or end of a reel. It also is caused by improperly threading the film into the reader, improperly reboxing the reel and rough handling in general. I had a client once send us a reel they described as “tarnished and splotchy.” Of course, we first suspected redox, but when the reel arrived, we discovered it was most likely catchup…so there is that too, I guess.

Damage does not just come from abuse but from just the act of using it as an access tool. Residual oils from the skin collect dust and other contaminants that are abrasive to the film leading to scratches and tears.

Even if your microfilm readers are properly cleaned and maintained and covered when not in use, it too can be a source of damage. Dust, oils, and particulates settle on the glass and are likely to scratch and wear the film with each use. Improperly seated glass platens, broken clutches, and sharp edges don’t help either…

At Advantage, we “practice what we preach” and use the only proven long-term preservation method for newspaper & document preservation: Capturing content on to 35MM silver halide archival quality microfilm. This polyester-based microfilm is the only medium currently recommended for preservation microfilming. Silver halide is a gelatin film based composed of very fine grains of silver and is the most light-sensitive of all the films used in microform. This allows the greatest amount of detail to be captured in the film and provides the richest tonal variance. Silver halide microfilm provides the most faithful reproduction of the source document. This stable and durable medium has a life expectancy of over 500 years under the proper storage and handling conditions.

Advantage Archives prides itself not only on meeting but exceeding ANSI/AIIM (Association for Information and Image Management) standards for the production, processing, and storage of this film as an archival medium. We also have built our process upon specifications once developed by the Research Libraries Group (RLG) and guidelines written by the National Archives, as well as the Library of Congress. This requires stringent adherence to internal Advantage guidelines regarding the careful production and examination of all archival microfilm, in addition to well-controlled storage and handling conditions.

We have embraced the idea that preserving history is a shared responsibility. We partner with local community publishers, institutions, and other like-minded individuals to ensure local history is preserved (and accessible) for future generations. We are very conscious of the fact that many institutions and government agencies face funding challenges and restricted budgets. Our goal is to ensure that a model exists to make those limited funds as impactful as possible.

We take the concept of “partnership” literally and share in the responsibilities of preservation and access that go far beyond the “project.” Call us to explore a partnership, and join us in our mission of: “Preserving the past, ensuring its future!”