The comic strip, a captivating blend of storytelling and visuals, made its debut in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, captivating the public’s imagination. “The Yellow Kid” holds the distinction of being the inaugural comic strip to grace the pages of North American newspapers. However, the origins of this charming and often overlooked art form stretch further back to the 1820s in Scotland.

It all began with “The Glasgow Looking Glass,” a publication crafted by the talented William Heath, which cleverly used satire to critique the Scottish socio-political climate. Through a slightly distorted but revealing lens, it humorously depicted the events of the time.

This modest Scottish publication, “The Glasgow Looking Glass,” stands as the pioneer of comic strips, marking the world’s first step into this narrative art form. Though it may have seemed inconsequential at the time, it planted the seeds of a genre that would flourish and evolve over the centuries, eliciting laughter from people across the globe. Its impact and influence are immeasurable, laying the foundation for what was to come.

At the heart of the comic strip’s evolution, the pioneering Swiss author and caricature artist, Rodolphe Töpffer, stands as a trailblazer, rightfully earning the title of the father of modern comic strips. Among his notable works, “Histoire de M. Vieux Bois” (1827), which later gained fame in the US as “The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck,” became a wellspring of inspiration for comic artists across continents, leaving an enduring legacy that profoundly shaped the art form.

As we fast forward to the year 1865, a new luminary emerged on the comic strip horizon – Wilhelm Busch, a multi-talented German painter, author, and caricaturist. In his creation, “Max and Moritz,” Busch crafted an amusing yet dark tale that chronicled the misadventures of two mischievous boys. The children’s stories of that era, which often featured harsh morality tales like Heinrich Hoffmann’s “Shockheaded Peter,” had a clear influence on Busch’s narrative. In a twist of fate, Max and Moritz met their gruesome end, ground in a mill and consumed by geese, a consequence of their roguish behavior.

Despite their unfortunate demise, these characters played a significant role in inspiring the creative minds of the artists that would follow. Artists who served as soldiers in the Newspaper War of the late 19th century.

The creation of “The Little Bears” by Jimmy Swinnerton in 1893 marked a notable milestone in the evolution of American comic strips. This delightful and endearing strip featured a lovable family of bears and became one of the earliest examples of recurring characters in sequential art. “The Little Bears” emerged during a crucial period in the newspaper industry’s history, coinciding with the intense newspaper rivalry between Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, commonly known as the “Newspaper War.” The competition between these media giants was at its peak during the 1890s, as both sought to attract readers and increase circulation.

It was within this fiercely competitive environment that “The Little Bears” found its place. Swinnerton’s creation offered a fresh and engaging visual narrative, capturing the hearts of readers with its charm and humor. The introduction of recurring characters in the strip allowed readers to follow the adventures and misadventures of the lovable bear family over time. This innovative approach proved to be a winning formula, as it provided continuity and familiarity, establishing a connection between the characters and the readers.

In the midst of this newspaper war, another pivotal moment in the history of comic strips unfolded with the creation of “The Yellow Kid” by Richard F. Outcault in 1895. This iconic comic strip, featuring a mischievous and street-smart child in a yellow nightshirt, became a sensation in Pulitzer’s newspaper, the New York World. “The Yellow Kid” was groundbreaking in many ways, including its innovative use of color to depict the central character in bright yellow, earning him his name.

Outcault’s “The Yellow Kid” holds a significant place in the history of comic strips as the trailblazer that marked the dawn of a new era in North American newspapers. This groundbreaking comic strip first made its appearance on the pages of Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper, the New York World, on Sunday, May 5, 1895.

What set “The Yellow Kid” apart and made it a sensation was not only its engaging storyline but also its innovative use of color. Outcault’s comic introduced the concept of using the then-new color printing technology to depict the central character in bright yellow clothing, thus earning the name “The Yellow Kid.” This eye-catching element not only captured readers’ attention but also became the strip’s defining visual characteristic.

The comic itself revolved around the mischievous and lovable Yellow Kid, a streetwise and cheeky child living in a working-class neighborhood. Outcault infused the strip with humorous observations and sharp wit, often portraying the Kid interacting with various colorful characters from the neighborhood. The dialogue and interactions between characters provided readers with a delightful insight into the everyday life and nuances of urban American culture during that time.

The Yellow Kid’s adventures and amusing escapades struck a chord with readers of all ages and backgrounds. It soon garnered a massive and diverse fan base, drawing people to the newspapers not just for news but also for the joy of following the Kid’s antics.

While “The Little Bears” predates “The Yellow Kid,” the latter’s fame and impact on American culture and the comic strip medium have led it to be often recognized as the first significant and influential comic strip in the United States. Both strips, along with others from that era, played crucial roles in shaping the evolution of comic art and its enduring popularity among readers.

To combat the success of the “Yellow Kid”, Rudolph Dirks, who was also influenced by the works of Wilhelm Busch, created the “The Katzenjammer Kids.” The strip debuted on December 12th, 1897, in the pages of the New York Journal, a newspaper owned by William Randolph Hearst. The comic strip quickly gained popularity beyond expectations, captivating readers with its humorous and mischievous adventures of the two rambunctious boys, Hans and Fritz, known as the Katzenjammer Kids. The comic strip found its roots in the visual style and narrative rhythm established by Busch with “Max and Moritz.” The mischievous antics of Max and Moritz resonated with Dirks, spurring him to develop a strip that captured the essence of playful mischief intertwined with humor and endearing characters.

Dirks’ “The Katzenjammer Kids” introduced several iconic comic strip elements that have since become ingrained in the genre’s fabric. Elements such as stars symbolizing pain, sawing logs representing snoring, speech balloons, and thought balloons all found their origin in Dirks’ strip. These creative innovations proved so fundamental to the comic strip’s language that they have endured through the ages, becoming inseparable from the realm of sequential art itself.

“The Katzenjammer Kids,” an unexpected hit, sparked one of the earliest copyright battles in comic strip history, highlighting the complexities of ownership in this emerging medium. Rudolph Dirks, the strip’s creator, left William Randolph Hearst for a more lucrative offer from Joseph Pulitzer. In the aftermath, a dispute arose over the rights to the name “Katzenjammer Kids,” with Hearst retaining it, while Dirks held onto the rights to the beloved characters. As a result, two versions of the strip, under different names, graced the comics pages for decades, illustrating how even legal conflicts can become sources of inspiration in the world of comics.

Another pivotal moment in the evolution of comic strips came in the latter half of 1892 when the Chicago Inter-Ocean newspaper published the first color comic supplement. This innovative use of color printing elevated the visual appeal of comic strips, making them even more captivating and attractive to audiences. The addition of colors breathed life into the characters and their adventures, setting the stage for a new era in comic art.

Amidst this backdrop of creative experimentation, William Randolph Hearst found yet another weapon to employ on the battlefield the Newspaper War was fought on. He fully embraced the potential of comic strips as a powerful draw for readers and in 1912, Hearst introduced the innovative concept of establishing the nation’s first full daily comic page in his New York Evening Journal. This visionary move allowed comic artists to showcase their talent and creativity on a larger scale, making comic strips a prominent feature in major American newspapers.

The introduction of the daily comic page marked a turning point for comic strips, as they became an integral part of newspapers’ offerings. It provided readers with a daily dose of humor, adventure, and entertainment, further solidifying the popularity of this unique narrative art form. This swift proliferation of comic strips in major American newspapers demonstrated the medium’s tremendous appeal and its ability to captivate a broad audience.

Thanks to Hearst’s visionary approach, comic strips seamlessly integrated into people’s daily reading routines, propelling the artists’ characters to soaring heights of popularity and sparking a comic strip frenzy across North American newspapers, with numerous publications eager to replicate the charm and draw of “The Yellow Kid.”

Due to the popularity of “The Yellow Kid”, the strip played a pivotal role in the fierce newspaper circulation wars between Pulitzer and Hearst. Both publishers recognized the comic strip’s ability to attract readers and compete for newspaper sales. Amidst the cutthroat competition for readership, both newspapers enthusiastically embraced flamboyant and sensationalistic reporting and employed attention-grabbing headlines. In this climate, comic strips thrived, serving as a delightful respite and a powerful tool for attracting and retaining readers amidst the fierce rivalry.

In an effort to capitalize on the Yellow Kid’s popularity Hearst, coined the phrase “yellow journalism,” for the aggressive and sensationalist journalism style, creating an implied connection to the Yellow Kid.

This opened a new front in the Newspaper War. The use of bold and provocative headlines, sensational stories, and a focus on crime, scandal, and human-interest stories characterized the era of yellow journalism. It often prioritized entertainment over objective reporting and blurred the lines between news and fiction.

While yellow journalism played a significant role in increasing newspaper circulation and readership during that time, it also sparked debates about the ethical responsibilities of the press and the need for objective and unbiased reporting.

Despite its negative connotations, yellow journalism also had an enduring impact on the evolution of modern journalism. It highlighted the power of the media to influence public opinion, leading to increased awareness of the role of journalism in society. Over time, journalistic standards and practices were refined, and the pursuit of accuracy and objectivity became core principles in reputable news reporting.

As the Yellow Kid gained immense popularity in Pulitzer’s New York World, it became a symbol of the newspaper and played a crucial role in attracting readers…right up until Hearst managed to hire Richard F. Outcault, away from Pulitzer. The protracted war waged in the pages of the newspaper began to spill over into the courtroom, and the conflicts intensified.

Outcault, at the direction of his new employer, began to produce a version of the Yellow Kid for the New York Journal, and for a period, a different version of the strip could be found in each paper. Pulitzer responded swiftly by claiming ownership of the character and filed a lawsuit against Hearst, asserting that “The Yellow Kid” was his intellectual property and that Hearst had no right to use it in the New York Journal. The legal dispute quickly escalated into a contentious and protracted battle, with both media giants fiercely defending their positions.

The lawsuit over “The Yellow Kid” highlighted the complexities of intellectual property rights, particularly in the emerging world of creative works like comic strips. It brought attention to the need for clear agreements and ownership rights in the newspaper industry, where creative talent could move between rival publications.

Beyond the ownership of comic strips, the rivalry between Pulitzer and Hearst extended to their newspapers’ content and reporting practices. Both publishers and their respective newspapers engaged in sensationalist reporting and aggressive tactics to attract readers and increase circulation. This led to a wave of libel and defamation lawsuits being filed against both Pulitzer and Hearst, as well as their publications.

Critics accused both newspapers of publishing false or misleading information to bolster their sales and manipulate public opinion. The lawsuits exposed the ethical boundaries of journalism and the need for responsible reporting. They underscored the importance of accuracy, credibility, and journalistic integrity in an era where sensationalism and yellow journalism were prevalent.

These legal battles and disputes during the Newspaper War period brought attention to the role and responsibility of the media in shaping public discourse and informing the public. They contributed to a growing public awareness of media manipulation and the importance of objective reporting. As a result, journalism standards and practices evolved over time, emphasizing accuracy, fairness, and adherence to ethical principles in news reporting. The legacy of these legal conflicts continues to influence media practices and discussions surrounding intellectual property and journalistic ethics to this day.

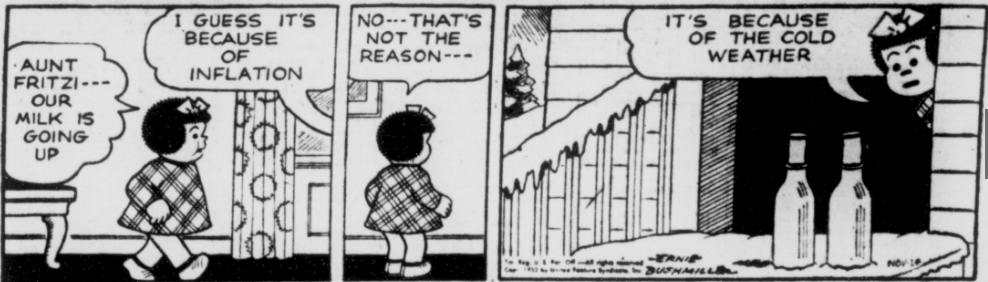

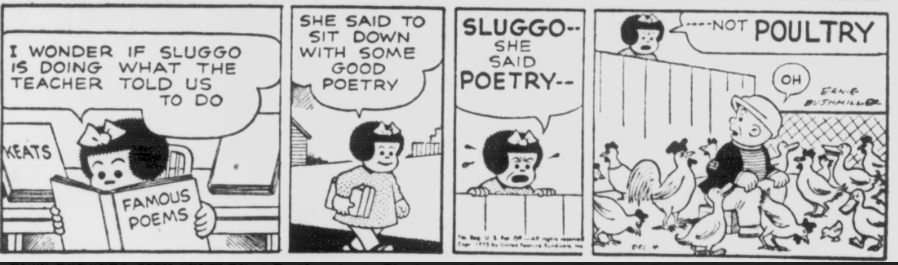

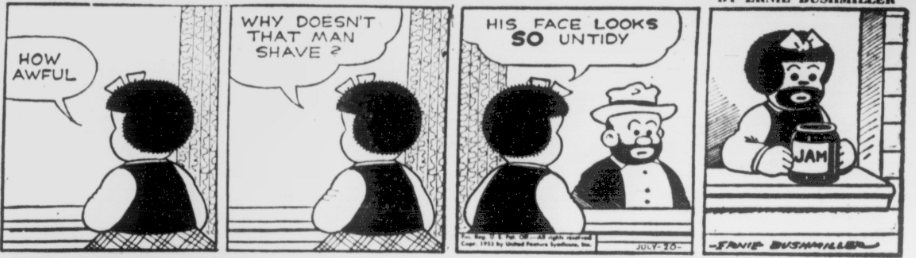

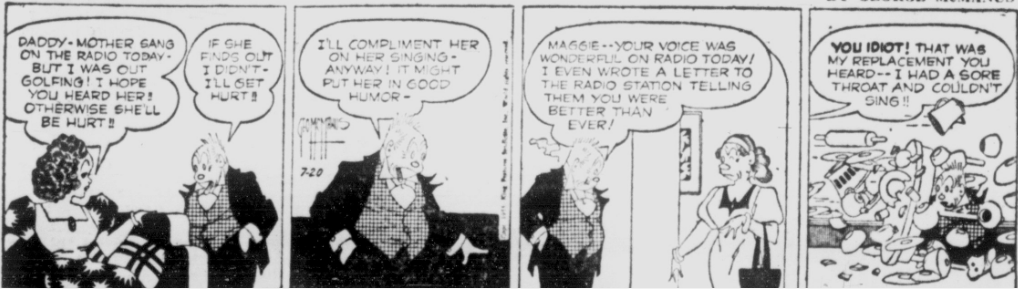

As comic strips continued to evolve and gain popularity, they transcended mere entertainment and began to comment on social issues, provide political satire, and reflect cultural trends. From the playful escapades of iconic characters to poignant commentaries on real-world events, comic strips have remained a cherished and enduring aspect of American culture, leaving an indelible mark on the nation’s media landscape.

As a result of his work with Hearst’s New York Journal, Richard F. Outcault’s career as a cartoonist continued to flourish despite his role in the conflicts created by his strip the Yellow Kid. Outcault reemerged in 1902, publishing a strip for the New York Herald.

The New York Herald, while not directly involved in the rivalry between Pulitzer and Hearst, was a prominent newspaper in its own right. It was founded by James Gordon Bennett Sr. in 1835 and had already established itself as a leading newspaper in New York City by the time the Newspaper War began.

During this period, the New York Herald continued to publish news and compete for readership with its own distinctive style and content. While it did not engage in the same sensationalist and aggressive tactics as the World and the Journal, the Herald still sought to maintain its standing as a respected and influential newspaper in the city.

With the addition of Outcault’s soon-to-become iconic “Buster Brown” comic strip, the Herald gained a tool to put the paper on the same stage as its contemporaries. This strip was written to align with the culture of the New York Herald, and it combined humor and entertainment with a strong emphasis on moral education. The strip quickly garnered attention for its innovative approach to engaging young readers.

At the heart of “Buster Brown” was the endearing and mischievous young boy, Buster, whose adventures often led to valuable life lessons. Accompanied by his loyal and intelligent dog, Tige, Buster navigated the challenges of childhood with wit and playfulness. Each comic strip followed Buster’s escapades, highlighting his interactions with family, friends, and authority figures, as well as the consequences of his actions. Rather than merely aiming to entertain, the comic strip sought to educate and shape the character of its audience. Buster’s misadventures were cleverly woven with life lessons, teaching children about honesty, responsibility, kindness, and the importance of making good choices.

Parents wholeheartedly embraced “Buster Brown” for its positive messages and ability to combine mirth with meaningful content. The strip’s emphasis on virtues and ethical behavior resonated with families across the country, who saw it as an entertaining and wholesome source of education for their children. The comic strip’s ability to make learning fun and relatable made it a welcome addition to many households, strengthening its popularity and readership.

Beyond the comic strip’s pages, “Buster Brown” quickly transcended its medium to become a cultural phenomenon. The character of Buster became widely recognized and was used in advertising campaigns, theatrical performances, and even as a popular figure in merchandising.

However, the World and the Journal remained locked in a cutthroat battle for dominance, which often overshadowed the Herald’s more restrained approach to reporting. The paper’s circulation growth was modest during the Newspaper War, yet the Herald maintained its reputation for reliable news coverage. The publisher’s integrity was no match for the sensationalism-driven tactics of its rivals. As a result, the Herald’s circulation gains, even with Buster Brown, were significantly lower than those of the World and the Journal.

Despite the challenges and overshadowing from its rivals, the New York Herald continued to hold its ground as a prominent and respected newspaper in New York City. It maintained a loyal readership that appreciated its more balanced and serious approach to reporting. The Herald’s legacy of quality journalism and its focus on delivering reliable news contributed to its enduring reputation as a reputable source of information.

The New York Herald ceased publication in 1924. In its later years, it faced financial challenges and decreased readership, leading to its eventual merger with the New York Tribune to form the New York Herald Tribune in 1924. The New York Herald Tribune continued to be published until 1966 when it, too, faced financial difficulties and ceased publication.

Instead of a clear winner, the Newspaper War between Pulitzer and Hearst is often viewed as a transformative period in journalism history, where competition led to increased innovation and engagement with readers. Their rivalry helped establish the American newspaper as a powerful medium for news, entertainment, and opinion, shaping the way the media landscape operates today.

The New York World continued to be published until 1931. However, its circulation declined significantly after Pulitzer’s death in 1911. In 1931, the New York World merged with the New York Telegram to become the New York World-Telegram. The World-Telegram continued to be published until 1966 when it ceased publication.

The New York Journal continued to be published until 1937. In 1937, the New York Journal merged with the New York American to become the New York Journal-American. The Journal-American continued to be published until 1966 when it ceased publication.

Renowned author Clive Barker once said, “There are no winners in war, only different degrees of loss.” This sentiment holds true in the context of the Newspaper War between media titans Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. Determining a clear victor between the New York World and the New York Journal proves challenging, as both newspapers fought fiercely for supremacy resulting in scars inflicted on the newspaper industry still visible today.

The heavy artillery in the Newspaper War came in the unlikely form of visual storytelling that combined illustrations with text to convey a narrative or tell a story. While neither publisher could be declared victorious, in typical wartime fashion, a heroic figure emerged from the conflict. That war hero was none other than Richard F. Outcault.

On the battlefield, Outcault was considered a formidable weapon both sides coveted and hoped to wield against the other. The rival newspapers sought to deploy his comic strip to boost their readership and circulation, just as generals deploy their artillery to secure crucial victories in the battle. “The Yellow Kid” was seen as a strategic hill that the rival factions sought to conquer and held immense value in the eyes of both generals.

The impact made by the “Yellow Kid” and the enduring popularity of “Buster Brown” not only solidified its place as one of the most beloved comic strips of its time but also cemented the legacy of Outcault as a pioneering artist in the realm of moralistic comics. The strip’s influence extended beyond its original run and left a lasting impact on the development of future children’s comics and media.

His legacy, forged in the heat of the Newspaper War, has shaped the ongoing success and appreciation of comic strips as a beloved and influential form of storytelling that continues to bring joy and laughter to readers of all ages.

The influence of comic strips is undeniable, with events in these strips often reverberating throughout society at large. For instance, from 1903 to 1905, Gustave Verbeek’s comic series “The UpsideDowns of Old Man Muffaroo and Little Lady Lovekins” was a marvel of ingenuity. Each of his 64 strips could be read, flipped upside down, and read again, creating a new narrative – a literal twist in the tale!

By the 20th century, at least 200 different comic strips and cartoon panels were a daily feature in American newspapers. The influence of these strips extended beyond newspaper pages, making appearances inside American magazines such as Liberty and Boys’ Life, and even on the front covers, like the Flossy Frills series on The American Weekly Sunday newspaper supplement.

Comic strips have come a long way since their mirthful origins in the late 1920s, expanding to include adventure stories and evolving into soap-opera-like continuity strips by the 1940s. Even though the term “comic” might suggest humor, not all strips tickle the funny bone. As cartoonist Will Eisner has suggested, “sequential art” might be a more genre-neutral name that embraces the diversity within the world of comic strips.

Whether we’re chuckling at the daily exploits in “Blondie,” following the misadventures in “Popeye,” or getting lost in the complex narratives of “Judge Parker,” it’s clear that the magic of the comic strip lies in its ability to captivate us through the fusion of images and text, making us return to it day after day, panel after panel.