In May of 1921, a young Black shoeshiner named “Diamond” Dick Rowland was involved in an “incident” involving Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white elevator operator at the Drexel Building in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Rowland had gone to the Drexel to use the top-floor ‘colored’ restroom, which his employer had arranged for use by his Black employees. A clerk at Renberg’s, a clothing store on the first floor of the Drexel Building, heard what sounded like a woman’s scream and saw a young Black man rushing from the building. The clerk contacted the authorities, and although the police questioned Page, she told the police that Rowland had grabbed her arm and nothing more. She declined to press charges.

Word of mouth accounts of the incident began to circulate, and the story was editorialized, exaggerated, and twisted with each retelling.

The embellished stories became the “truth” for the white community when one sensationalist version of the account was printed in Tulsa’s paper of record. The Tulsa Tribune published an inflammatory article with the headline: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator,” on May 31st, enraging the white community. Police arrested Rowland the same day.

Shortly after Rowland was taken into custody, hundreds of armed white men gathered around the courthouse where Rowland was being held, leading to a confrontation with a group of around 75 Black men. The Black men, some of whom were armed, gathered at the courthouse because rumors circulated that Rowland would be taken from the police and killed. They were determined to prevent the crowd from lynching Rowland.

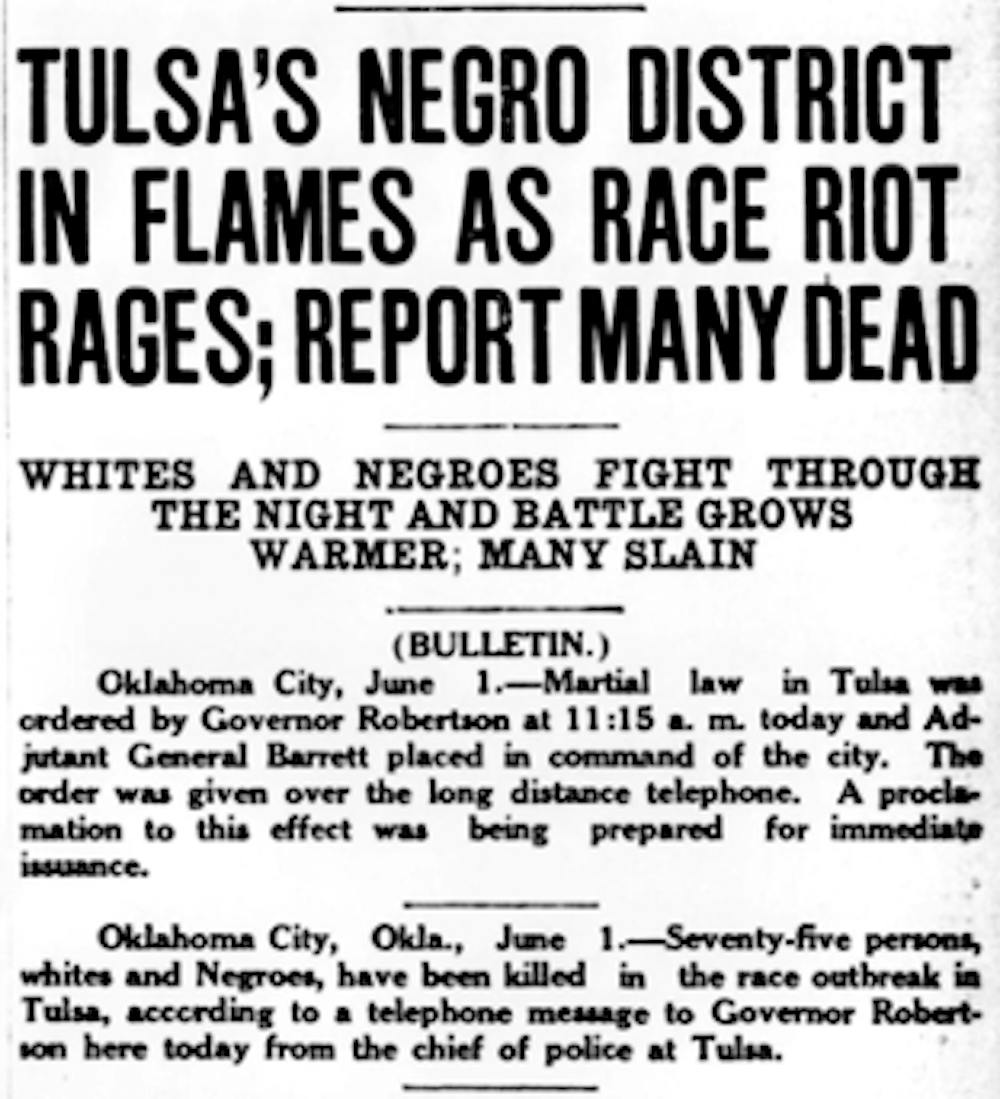

The conflict between the two groups escalated, and shots were fired. At the end of the exchange of gunfire and ensuing violence, 12 people were dead, ten white men and two Black men. The deaths raised the stakes even higher, and the Black men knew that they were outnumbered, so they retreated to the Greenwood District. The white mob, some of whom had been deputized and given weapons by city officials, pursued the Black contingent toward Greenwood. Chaos ensued as White rioters shot indiscriminately and killed many residents along the way, looting homes and businesses before setting fire to them.

Several residents later testified the rioters broke into occupied homes and ordered the residents out to the street, where they could be driven or forced to walk to detention centers. Six thousand people were held at the Convention Hall and the Fairgrounds, some for as long as eight days.

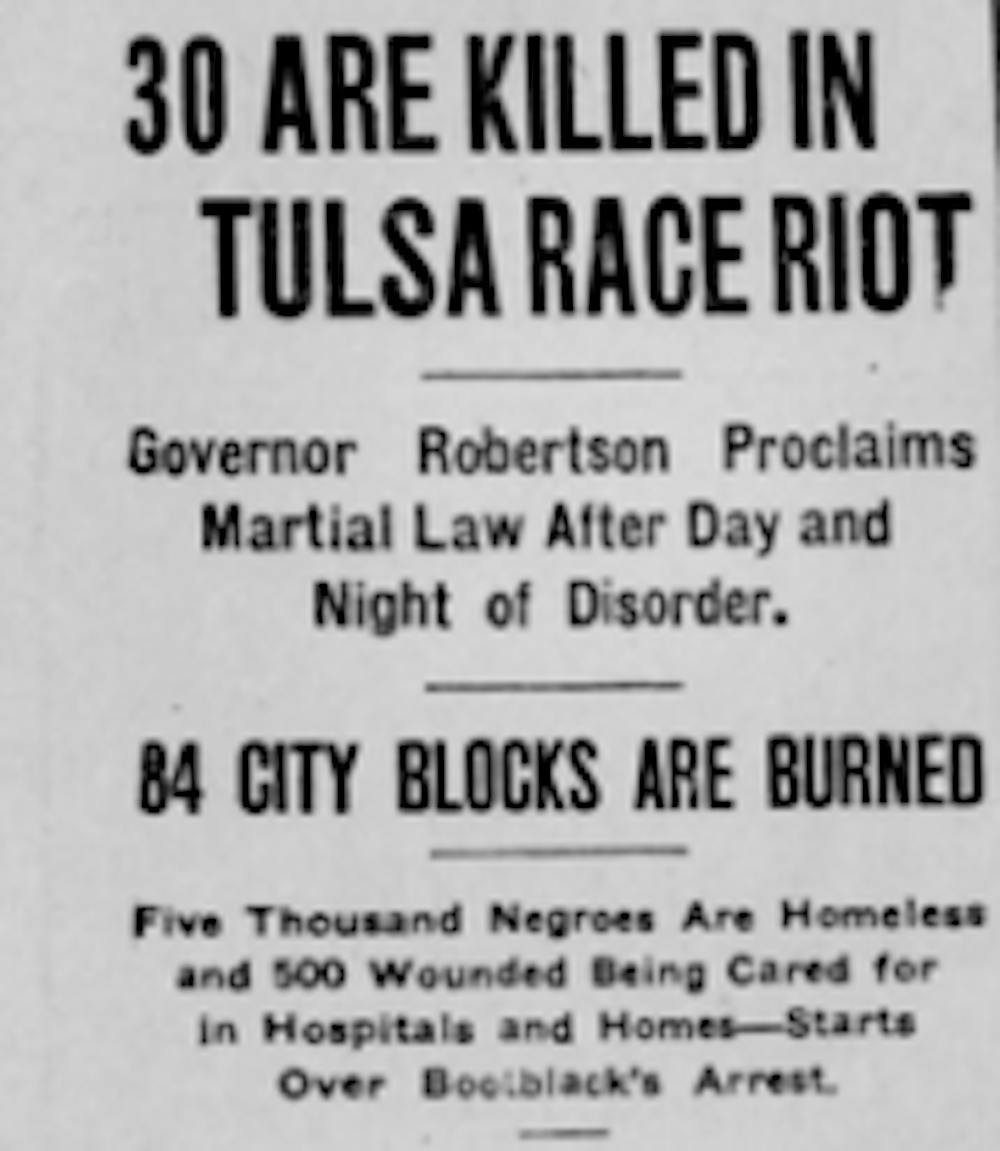

Greenwood was one of the wealthiest Black communities in the United States, known as “Black Wall Street,” and by noon on June 1st, 1921, thirty-five city blocks lay in charred ruins. Losses included 191 businesses, a junior high school, several churches, and the only hospital in the district. The Red Cross reported that 1,256 houses were burned, and another 215 were looted but not burned. The Tulsa Real Estate Exchange estimated property losses amounted to $1,500,000 in real estate, equivalent to around $24,000,000 today. Over the next year, local citizens filed more than $1,800,000 ($29 million in 2022) in riot-related claims against the city.

Tulsa Chief of Detectives James Patton attributed the cause of the riots entirely to the newspaper account published in the Tulsa Tribune and stated, “If the facts in the story as told the police had only been printed, I do not think there would have been any riot whatsoever.”

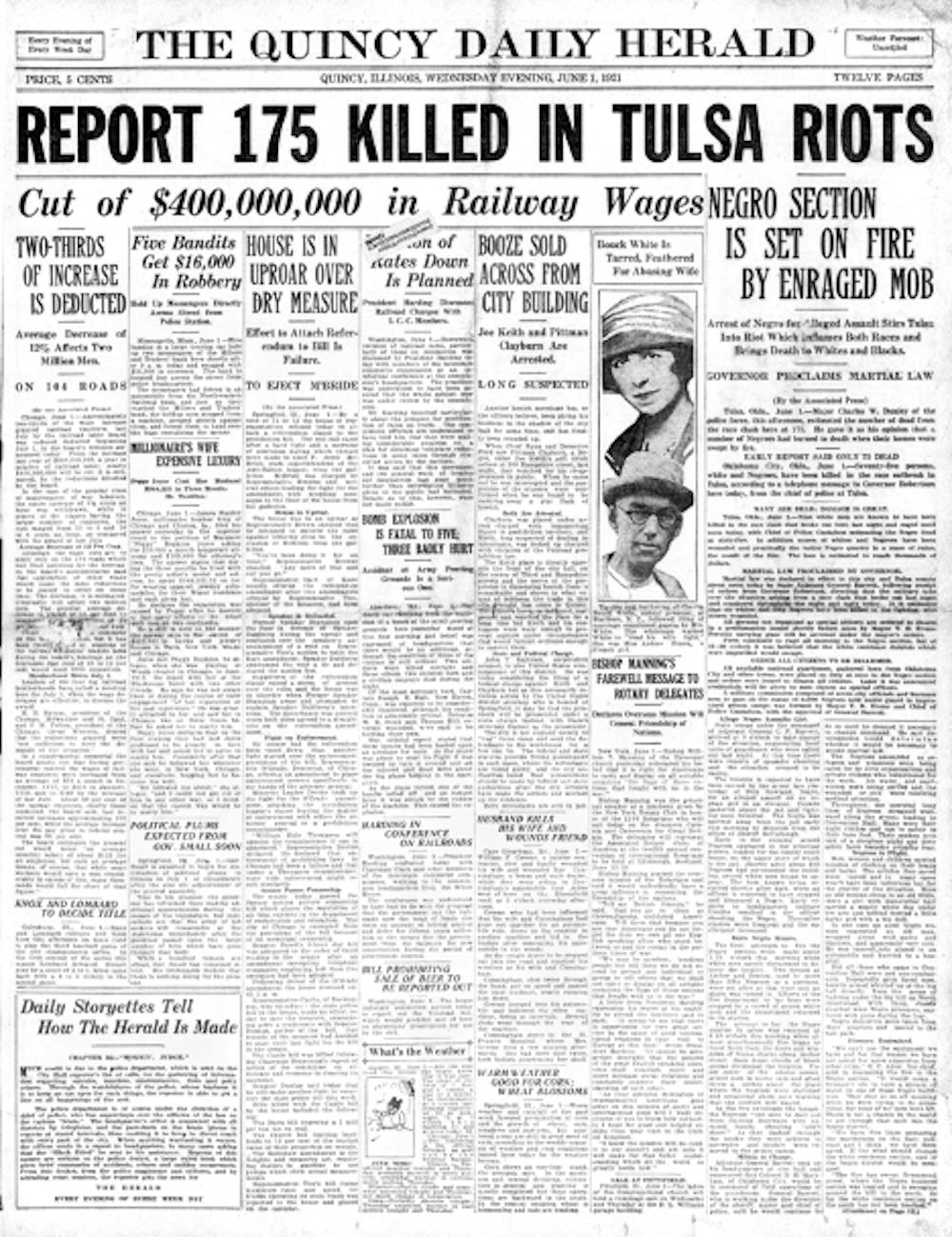

Ten thousand people were made homeless by the destruction. More than 800 people were treated for injuries, but the number of deaths reported varied wildly from publication to publication.

Newspapers reported as few as 15, and as many as 175 were killed. Historians now believe as many as 300 people may have died, but in the days after the massacre

The article being torn out of the front page of the May 31st Tulsa Tribune is disappointing, disturbing…but unfortunately not surprising. All original copies of that issue of the paper are believed to have been destroyed, and the relevant page is missing from all available microfilmed copies.

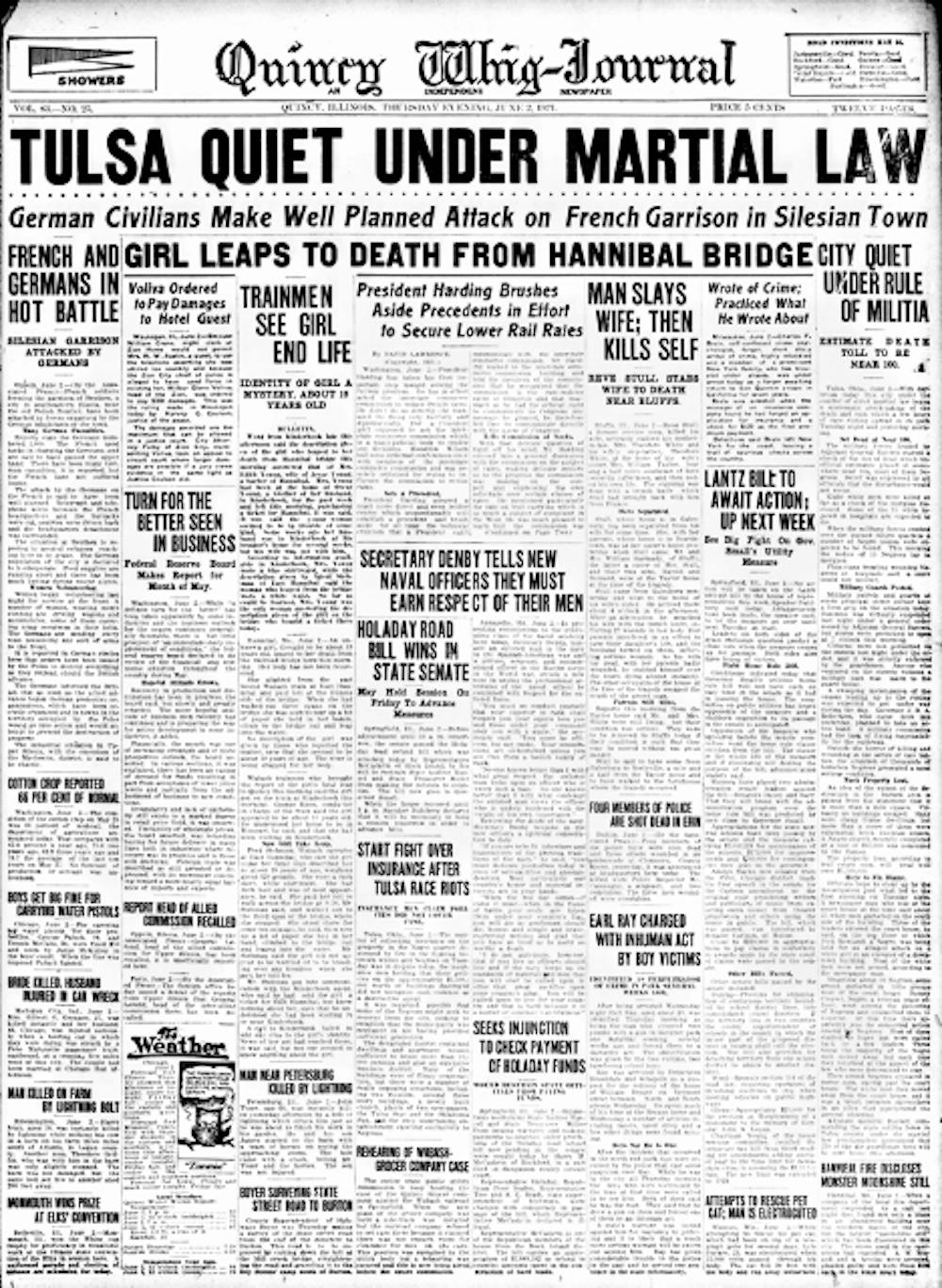

There were no convictions for any charges related to the massacre and decades of silence about the terror, violence, and losses. Although newspapers across the county published articles, in some cases, it wasn’t reported for days, and even then, it was often not even featured on the front page. Like this “blurb” found on page Page 2 of The Independent, published in Forest City, Iowa on Thursday, June 9th.

Coverage faded quickly, and it was extremely rare to find any references to it by July of 1921. The massacre was largely omitted from local, state, and national histories. The Tulsa race riot was rarely mentioned in classrooms, or even discussed in private. Black and white people alike grew into middle age, unaware of what had taken place”. It was not recognized in the Tulsa Tribune feature of “Fifteen Years Ago Today” or “Twenty-five Years Ago Today.” A 2017 report detailing the history of the Tulsa Fire Department from 1897 until the date of publication makes no mention of the 1921 massacre.

In 2001, an official Race Riot Commission released their disappointing conclusion: “No one will ever know the absolute truth of what happened during the hours of, and leading up to the Race Massacre.” However, by examining historical resources, members of the Race Riot Commission determined the number of details to be undeniable. “These are not myths, not rumors, not speculations, not questioned. They are the historical record.”

To understand any of this, we must see the events through the lens of the men and women that lived this history and read about it in their words. We learn a great deal about the prevailing attitudes, emotions, prejudices, and justifications…even though it is sadly one-sided in the vast majority of America’s early newspapers. Preserving and providing access to this unvarnished and unrevised “first draft of history” is not just about the past but also our present and our future. We can see how far we have come…and, in many cases, how much further we still have to go.